This post originally appeared on Heather Marquette’s blog, at heathermarquette.wordpress.com

In a recent guest post for Duncan Green, ODI’s Alina Rocha Menocal asks whether learning to ‘think politically’ is like learning a new language. It’s a great analogy and one that should be taken seriously. As she points out, in order to learn this new language – incentives, rules of the game, values, rents, complexity, power and so on – ‘A radical approach is needed – much akin to learning a new language from scratch, within a conducive environment that fosters adaptation, flexibility, ingenuity, and the ability to learn by doing.’

None of these are things that donor agencies are renowned for doing well, as anyone who has read Thomas Carothers and Diane de Gramont’s wonderful book or the recent ICAI report on DFID’s ability to learn will tell you.

But Alina’s analogy needs to be taken further to understand just how important it is and how challenging the implications are for donors, or any development organisation that employs a large number of technical staff with no specific remit to focus on politics. And it has to do with how we learn languages.

One of my younger brothers, Joe, is a linguist. He’s fluent in over 10 languages, can speak at least 10 or 15 to a high level. He doesn’t just speak Italian, he speaks several Italian dialects as well. He can speak French with a Parisian, Quebecois, Dijonnais or Breton accent. He has taught himself to speak Arabic, Hindi, Mandarin, Welsh, Afrikaans, Dutch, ancient Greek, modern Greek. Not well enough to conduct delicate trade negotiations but more than well enough to tell a joke, read the paper, talk about love and food and dreams. He rarely dreams in English anymore.

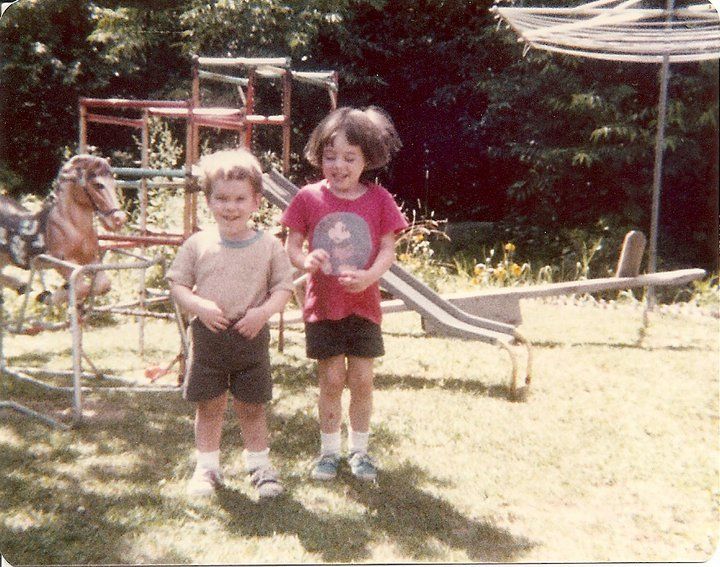

He did this growing up in rural New Hampshire in a pretty monolingual family and certainly in monolingual schools, but surrounded by older family members who still spoke the languages of their birth. While other boys read comic books, he read dictionaries. While other boys played baseball, he learned how to cook a delicate ragu and how to speak both Italian and Sicilian.

And he was a giant pain in the ass about it. He just stopped speaking English, no matter how important the conversation was. He refused to answer the phone properly, despite it being our father’s lifeline for his business, and he cost our dad terribly in terms of lost opportunities during a deep recession. He was a target for bullies, and I spent an inordinate amount of time as his big sister standing up for him. But no matter what, he kept speaking only in whichever language he was learning at the time, because he knew – even at 10 years old – that the best way to become fluent in a language is to become fully immersed in it. You don’t learn best in a few days in a classroom, and you don’t learn best from a book. You learn a language best by being thrown in the deep end. Thirty years later, he’s a much loved sibling and son, a fantastic travel companion and an exceptionally gifted linguist and teacher.

There are likely to be at least four different types of learners in development organisations that hope to get their staff ‘thinking politically’:

- ‘Children’ – those staff who are new to the organisation and are open to a new way of working and a new way of thinking and will take to training like a fish to water. They’ll still benefit from ‘immersion’, of course, but there’s likely to be less resistance to new ways of working.

- ‘Adults’ who have some background in politics or who have an innately political brain – those people who ‘get’ politics easily in whichever country, or whichever situation, they’re in and who just see the world in this way. They’ll also take well to training and will be able to internalise it and will become the ‘mavericks’ who figure out how to work around organisational systems in order to get things done. They’d probably do this, with or without training, because it’s how their brains operate.

- ‘Adults’ who understand that this new language is important and will try their best but will always struggle to do more than the basics – those people who will enjoy the training, who will leave with the training materials and will do their best for a few weeks but who’ll eventually fall back into their old ways of working once they’re no longer in class. They know it’s important but just can’t seem to figure out ‘what to do differently on a Monday morning’ without a teacher there to help. They may become cynical, because they know they’re probably not working in the best possible way but don’t know what to do faced with their everyday working realities.

- ‘Adults’ who don’t get it, won’t get it, don’t want to get it – those people who are the equivalent of tourists shouting, ‘DO YOU SPEAK ENGLISH?’ at people. They have their ways of working. They’ve been doing what they’ve been doing in the way they do for a long time and don’t see why they should change. They’re experts in their fields, at the cutting edge for what they do. They just don’t ‘think politically’ and don’t see why they should have to try. And trying to get them to learn a whole new technical language is never going to work.

Right now it seems like we have a one-size-fits-all approach to encouraging ‘thinking and working politically’, and it’s not based around any sort of pedagogical approach to changing adult learners’ behaviour, and it’s definitely not based around what we know about learning a new language. We have political economy analysis (PEA) training in the classroom, usually in short courses of 2-3 days at that, and with some course texts and material to take away. Or maybe an online course where they’re on their own. These may be fantastic courses – interesting, engaging, thought-provoking. And for the first two types of learners, it may be just enough to get them started.

But for actual transformational change in the way that donors and other development organisations work, all types of learners need to engaged with. And if this isn’t possible, then the goal posts need to shift.

Should organisations focus on the ‘children’, making sure that all new staff learn new ways of thinking and working (recognising that when they go back to their monolinguistic silos, they may irritate others and may even face bullies)? Should they focus on particular types of programs and certain types of staff and forget about the rest? Should they hire new people with the right skills and mind set, possibly using some psychometric testing (though what happens to existing staff)? Should they focus on finding opportunities for immersion – putting staff in a country for long enough to really learn the language of politics there (though what happens to technical staff or external experts who advise on projects in multiple countries)?

Alina is absolutely right that learning to think and work politically is like learning a language and that this is a radical approach. It changes how we think about existing training, where it isn’t about capacity building or ‘skilling up’ but rather behavioural change and so needs a radically different approach to the one we have now. But it also raises questions about the types of staff that development organisations currently have and whether or not they’ll all be able (or willing) to take on board this agenda. And if not, what do we do with them?

It’s the difference between ‘Je parle politics’ and ‘Je ne parle pas politics. Je ne suis pas désolé’ and all of those staff in between. And a one-size-fits-all approach to learning won’t make them all fluent any time soon.