Image: Jakarta skyline (Photo: ‘Hotel Addict’ Yohanes Budiyanto, Flickr).

When your office is in Jakarta, you get a lot of time to day-dream in taxis while going from hotel to office and back again. I am just back from a couple of weeks working there and I marvelled at the traffic, the tech-savvy population and the profusion of swanky hotels. On one long journey I got to musing about the challenges facing Indonesia’s efforts to shift itself upwards in the World Bank’s country classification database.

The latest estimates of Gross National Income per capita published on 1 July rank Indonesia as a lower middle income country (LMIC) for the second year running.

The government’s ultimate aim, of course, is to get Indonesia into the HIC – high income country – club. Yet efforts to encourage continued economic growth there seem to me to face three critical policy and institutional challenges:

- The economic challenge will be how to maintain high rates of growth while facing increasing economic competition from countries with cheaper labour, and how to increase productivity and performance from the adoption of more complex technology.

- The political challenge will be how to replace what have historically been patronage-based and authoritarian regimes largely taking decisions for personal and private gain, with increasingly rules-based, formalized and publicly accountable governments taking decisions for the public good;

- The social challenge will be how to respond to a larger, more demanding and vocal middle class with rising aspirations; how to respond to demands for greater inclusion and equity as awareness of income and wealth disparities grow; and how to meet the economy’s need for a more educated workforce with higher levels of skill.

I considered these challenges while returning from a one-day workshop on the nature of political settlements. I gazed out of the taxi as a locust-like swarm of motor-bikes swept past and wondered: if economists can have their middle-income trap, can political scientists (even pretend ones like me) have a political settlements trap?

It might go something like this. With economic growth and structural transformation, a rising middle class will place additional demands on the state. Increased literacy and media coverage will increase awareness of inequality and so challenge current political and economic elites. Then the political dynamics and internecine struggles involved in ‘resettling the political settlement’ will involve complex and possibly transitory political alignments, alliances and conflicts, and some of those conflicts will be violent.

From a high-level, country governance perspective, Indonesia’s decision-making system needs to make a number of shifts:

- from informal and personalised to a more formal and increasingly rules-based system;

- from a focus on private gain or rent-seeking to a focus on the public good; and

- from the generation of extreme wealth for the few to the generation of prosperity for the many.

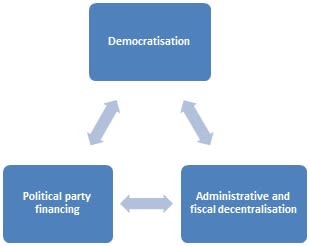

So what are the chances of the political settlement being renegotiated in Indonesia’s current policy context? After ten days in Jakarta I was profoundly struck not only by the gridlock on the streets, but by that lack of potential for the kind of movement that would promise positive change. There are already three major drivers ‘resetting’ Indonesia’s political settlement that are creating a ‘triple lock’:

- Fiscal and administrative decentralisation – In 2015, 31% of Indonesia’s budget will flow to subnational levels of government and administration, compared to 32% spent nationally. This proportion will increase significantly as flows directly to villages come on line.

- Democratisation – Ten years ago there was one election every five years; today there are about 550, and new administrative units are proliferating in response. For example, in 2000 Papua was one province and 10 districts. Today it consists of five provinces and 72 districts.

- Money politics – The cost of getting elected is increasing and political parties are financed mainly by oligarchy funding rather than membership fees or state funding.

This triple lock creates enormous opportunities for rent-seeking. I have been told that the trade in bureaucratic jobs, controlled at senior levels by the Ministry of Home Affairs, is worth about $1 billion per annum.

The interplay of these drivers has fundamentally changed Indonesia’s political economy over the last 10 years: the older structure of power and influence is being dismantled and a new one has emerged. Power is now spread and shared – and the growth in the economy and the size of the budget admits more power holders, and simultaneously increases the incentives to get in on the act.

So the (informal) rules of the political and bureaucratic game are changing, but mostly in a damaging way: the incentives and norms now being institutionalised are inimical to policy-making and implementation for the public good. These incentives are changing rapidly – but they seem already to be established.

This creates a challenging the environment for a more rules-based, formal public service operating for the public good. Clearly no system – and no political settlement – exists in a vacuum. Indonesia’s public service has all its own incentives, inefficiencies and incompetences, and the public service itself is enveloped within those triple-lock drivers.

It is not surprising, then, that many externally financed initiatives find they are ‘going against the grain’. And losing. It is difficult to see how service delivery and public sector performance can counter these new dynamics.

By this time my taxi had, at last, reached my rather unswanky hotel, so I went in and had a calming bath and a cold beer.

See more posts on political settlements by researchers, policy-makers and practitioners.