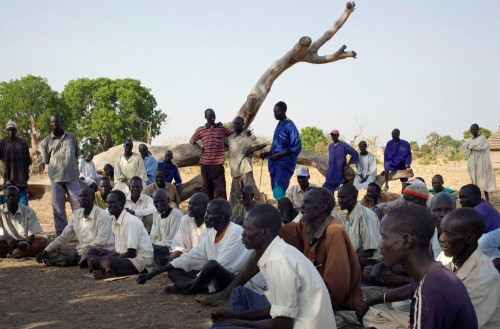

Image: A traditional court in South Sudan (UNDP South Sudan / Brian Sokol).

Donors are keen to improve the safety, security and access to justice of the people they are trying to help. But the British and Australian governments, the World Bank and the European Commission all admit that their programmes have not come close to achieving the ambitious security and justice agenda set out in policy statements and donor guidance documents, such as OECD-DAC’s Handbook on Security System Reform.

Why? Because donor approaches remain overly technical and insufficiently political. Programmes generally focus on building the capacity of state security and justice institutions.

As I note in my recent paper, Security and Justice: towards politically informed programming, security and justice are core state functions. They are a key source of power for elites. So it’s not surprising that their control is often contested by an array of actors, ranging from national state institutions such as the police and military right through to local community-level providers such as chiefs, militias and vigilante groups.

Policy-makers, donor staff and the academic community have all been grappling with the challenge of how to ‘work politically’ in security and justice assistance. There is recognition that political elites must be engaged in the process, but that tensions between the interests of elites and citizens have to be considered. Complex political dynamics and power relations need to be understood, from the national to the local community levels.

A politically nuanced approach calls for a better understanding of context, engaging with local stakeholders on a more equal basis, and ensuring that objectives are realistic and projects can respond to changing circumstances. There is nothing particularly new about these good practice principles, all familiar to anyone with experience in the development sector. Policy-makers, practitioners and academics have been advocating these principles for years.

In my experience in this sector, nothing has ever suggested that donor staff were not aware of these principles. At the security and justice practitioners’ courses that we ran at the University of Birmingham from 2010 to 2012, for example, many of the participant discussions focused on this very issue.

Yet a policy-practice gap persists. The situation we find ourselves in was perhaps best summed up in a debate amongst the security and justice community as part of an e-conference back in 2009. Participants recognised the mismatch, accepted that change is needed, and that there was a limited but growing evidence base on which to base programming decisions. So far, however, donors have not been able to apply what they’ve learned, or translate policy into practice.

Why might this be the case?

One problem is that security and justice programming is a particularly high-risk area. It is arguably one of the most ‘political’ of all areas of development assistance. Often, donors are operating in fragile and conflict-affected contexts with rapidly changing political dynamics, corruption and violence. Security and justice actors, whether national or local, may not buy into democratic governance and human rights norms – they may even be responsible for human rights violations. It is understandable, then, that working with these actors and justifying that work to a domestic audience is challenging.

Because security and justice programming is so politically sensitive, the ‘right’ people are needed for this kind of work. They need to have good knowledge of the local context. They need the political skills to deal with the often competing interests of a range of actors. Building such skills and knowledge takes time. It can’t be done when there is high staff turnover, and this is often a problem because of the difficult, complex environments where security and justice assistance is generally directed.

So what is the way forward? There are no easy answers. These issues present real dilemmas for donors.

However, one way forward would certainly ask donors to become better at sharing knowledge, and then at applying learning to programming. Donors are aware that they need to improve in this area.

But it’s also fair to say that the body of evidence for security and justice programming is weak. There are evidence gaps in several areas, including:

- the role of political leadership in bringing about reforms and transforming organisational cultures;

- evaluations of donor engagement with non-state and local community-level actors;

- how to apply to security and justice programming the lessons learned from working politically in other development sectors.

Security and justice is still a relatively new concept; it only emerged on the donor agenda in the late 1990s. The evidence base will improve over time. But closing the policy-practice gap will still ultimately depend on donors being able to translate this learning into practice.