Image: One of the Daru settlements where many visitors from South Fly Villages stay, Mark Moran.

This blog was first published via The Conversation on 12 April 2020

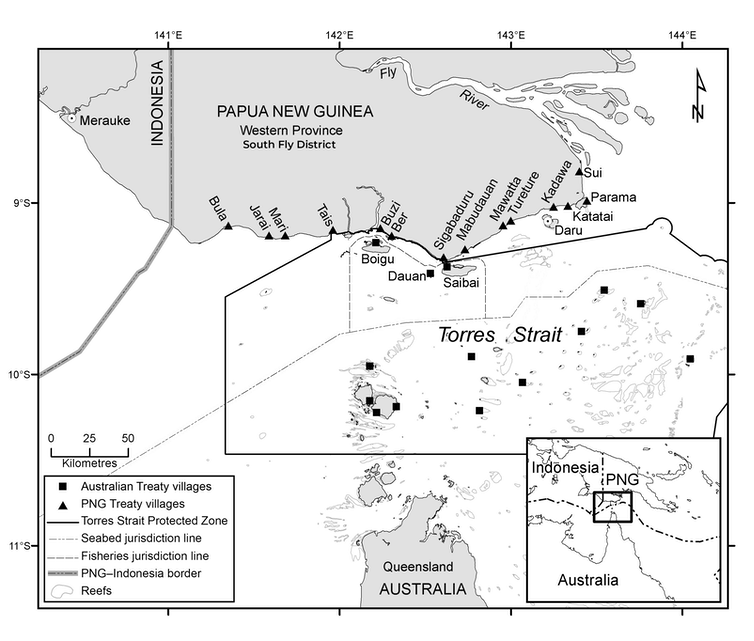

Less than four kilometres from Australia’s northernmost islands in the Torres Strait lies the South Fly District of Papua New Guinea.

If you’ve ever heard anything about this borderland region – wedged between Australia, Indonesia and the Fly River in southern PNG – it’s likely about protecting Australia from disease, illegal migration, drugs and gun smuggling.

However, the story of the South Fly District is much more complex. It is a story of chronic underdevelopment and growing frustration with a border management regime that favours some PNG nationals over others and ever-tightening restrictions on trade across the Australian border.

Over the past four years, researchers from the University of Queensland visited 35 South Fly villages and five Torres Strait islands to better understand the relationship between the two sides of the border. The findings were just released as a book, Too Close to Ignore: Australia’s Borderland with Papua New Guinea and Indonesia.

A map of the South Fly District in southern PNG and neighbouring Torres Strait Islands. Author provided

Extreme poverty on the PNG side

The World Bank has set the international poverty line at A$2.70 per person per day, but the median income in South Fly villages is less than half of this. Worse still, basic goods like flour and sugar are twice what people pay in remote areas of Australia, and the cost of fuel is A$3–4 per litre.

PNG is often described as having a dual economy, with mining and other foreign investment driving the main economy with money, and subsistence gardening underpinning the other. Subsistence activities (growing only what is needed for survival) remain essential in rural areas where more than 80% of people live.

But cash is also desperately needed for basic food items, health services and schooling. People are constantly looking for markets, but they face formidable obstacles due to the remoteness of the region and high transportation costs.

Now, the hardening of the Australian border is proving to be another barrier, too.

A South Fly Village house with an improvised door (scavenged from the Torres Strait). Author provided.

Hardening of the border

To stem any threat of coronavirus, cross-border travel with the exception of medical emergencies has been banned since mid-February, more than a month before PNG’s first confirmed case.

But even before then, a complex border management system was fuelling frustrations.

Under the Torres Strait Treaty, residents of 14 nominated “treaty” villages in PNG have been allowed to cross the border, so long as they have a pass signed by a Torres Strait Island councillor.

Passage is limited to traditional purposes only, which is interpreted by Australian authorities to exclude commercial trade. South Fly residents, however, still seek to barter across the border for cash and goods. This trade is critical to their economic survival.

For PNG residents, the Australian government approach to border management relies on a hierarchy of haves and have-nots — those villages with treaty status, and those without.

As non-treaty villages can’t cross the border, they sell their goods to treaty villages, who then on-sell them into the Torres Strait. The treaty villages guard their privileges, informally helping to manage the border.

But the treaty villages themselves are now also struggling to trade, as the Australian Border Force (ABF) and Torres Strait Island councillors have, in recent years, asserted more control over the border.

By not issuing passes, the councillors limit the numbers of days for visitors and even issue total bans to entire villages. They do so to protect their limited resources during times of water shortages, to prevent the spread of infectious diseases or viruses (like COVID-19), or as punishment for overstaying on previous visits, fighting or other breaches.

The Australian government relies on the councillors to be informal frontline defenders of the border. ABF officers have also imposed harsh restrictions on those who do manage to cross, including limits on access to ATMs for PNG visitors trying to collect remittances from extended families.

PNG visitors are no longer able to sell their goods or avail themselves of medical services to the extent that they once did, either.

Border management trumping aid assistance

This system has some kind of logic for border control, but it makes no sense when it comes to other issues, like health.

Australian aid assistance in the South Fly District is largely limited to the capital Daru and the 14 treaty villages. In these regions, Australia has funded a world-class response to tuberculosis, including a hospital in Daru and health centre in Mabuduan, a treaty village.

The primary health system in the rest of the district, meanwhile, is grossly understaffed and under-resourced. People from South Fly villages often travel to health clinics on the outer Torres Strait Islands, where clinicians adopt a humanitarian position for medical emergencies.

If patients have TB, they are sent back for treatment at the Daru hospital. But the health system’s transport is extremely limited, and most PNG residents can’t afford the exorbitant cost of fuel for private dinghies.

When they can raise the money to travel to Daru, they are often accompanied by family members and stay in squalid, overcrowded housing, where they run the risk of further spreading or catching TB.

Normalise aid spending for greater impact

Despite the long history of reciprocal relationships between the South Fly and Torres Strait, a hardening border is worsening destitution and on the PNG side and exacerbating the security threat to Australia.

And as the Australian border hardens, the Indonesian border beckons, where trade in mostly dried fish products has been long established. Compared to the Australian border, the PNG-Indonesia border is relatively porous, and illegal border crossings and overfishing are pervasive.

Allowing commercial trade across the PNG–Australian border would certainly help. For example, the crab trade has been dominated by Chinese store owners in Daru, who buy up everything until stocks are depleted to sell onward to Singapore.

Building a crab fishery in the South Fly could be a profitable enterprise for Torres Strait Island businesses, with live exports sold to restaurants in Australia, and better prices paid to the PNG women who traditionally catch them. Australian quarantine officers in the Torres Strait Islands could control catch size.

Expanding the bilateral aid program to benefit all the villages in the district, not just treaty villages would also help.

The current money needs to be dispersed more evenly for greater impact, according to the principles of aid effectiveness and population health, and not play “second fiddle” to border management.