We are sitting around in an office in Honiara. The traffic is moving slowly past the window in the evening ‘rush’. A hand of bananas is the table centrepiece. It gets smaller as the pile of skins grows. It’s hot, but not too hot. Voices alternate around the circle. Laughter, whispers, laughter, a serious tone, a friendly joke. We are having tok stori to plan a conference.

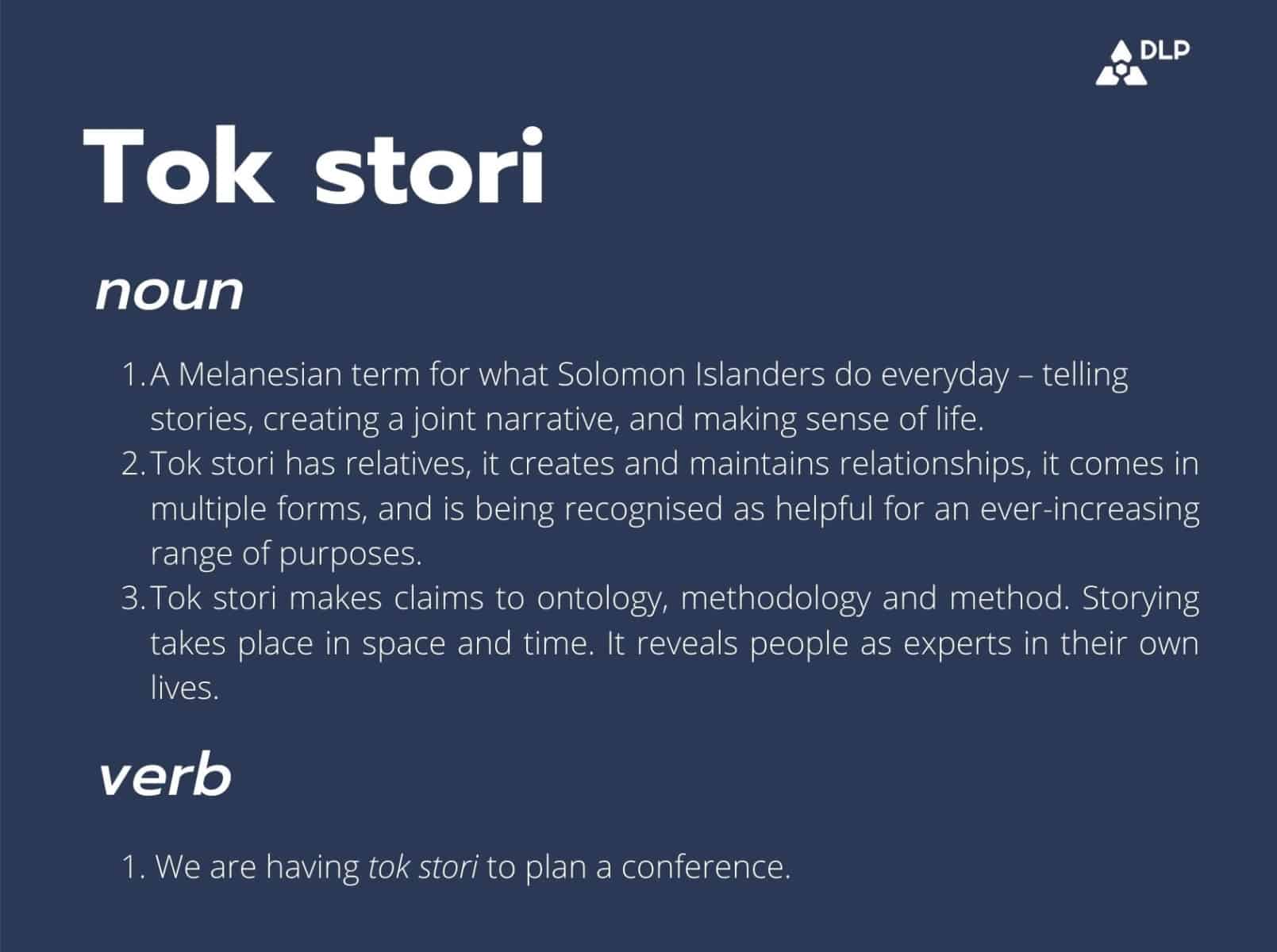

Tok stori is a Melanesian term for what Solomon Islanders do everyday – telling stories, creating a joint narrative, and making sense of life. But that’s not the whole story. Tok stori has relatives, it creates and maintains relationships, it comes in multiple forms, and is being recognised as helpful for an ever-increasing range of purposes. (For more on this, check out the authors’ article ‘A tok stori about tok stori: Melanesian relationality in action as research, leadership and scholarship’.)

There are many forms of orality in the world. Kovach points at the constellation of Indigenous conversational modes of storying through which knowledge is developed, collected and transmitted. These include Australian Aboriginal yarning, Hawaiian talkstory, talanoa which is at home in Tonga, Samoa, Fiji and elsewhere, and more. Telling stories demands participation, it involves dialogue. Storying textualises our experiences and assists others. In our tok stori, we listen, share and respond. We enjoy our deepening relationality as we negotiate the final conference details.

Tok stori makes claims to ontology, methodology and method. Storying takes place in space and time. It reveals people as experts in their own lives. Collaboration, informality and flexibility, purposefulness and locatedness; these all assume significance. When we story, we embody our social self and deepen our connections in a dialogical universe. We know we are in a safe space. (For more on this, check out the authors’ article on ‘Melanesian tok stori in leadership development: Ontological and relational implications for donor-funded programmes in the Western Pacific’.)

Tok stori in action in the Solomon Islands. Image credit: Kabini Sanga.

Some researchers have paid attention to myriad forms of tok stori in Melanesian villages. These range from the storied revelation of secret knowledge destined only for the few, to retellings of day-to-day activities for the amusement of actors and any passing listeners. Beyond the village, and in addition to groups of friends trading experiences, the potential of tok stori as a form of engagement is being recognised in fields such as informing policy and implementing pedagogy. Like everybody else, Melanesians like to do what they know, and are good at what they practice. That is precisely why outsiders should take notice of tok stori.

Here’s a story. A friend of ours recalled angst during her PhD in a time when the scholarship of tok stori as research was thin. From PNG, but studying in Australia, she was advised to investigate using closed questions and Likert scales. Tired of positive responses she knew only represented a desire to give her the answers people thought she wanted, she went to a party. She spent the whole night in tok stori with some of her respondents and their friends. She lost sleep, but found among the lived experiences and world views of those young people what she was looking for. Her research would never be the same again.

Leadership development is also a fruitful field for tok stori. In the past, Solomon Island school leaders have been upskilled using introduced frameworks. But diversity is the hallmark of Solomon Islands education, and a one-size-fits-all model is unhelpful. A recent programme, the Graduate Certificate of School Leadership, used tok stori as pedagogy. Mentors threaded theoretical conceptualisations clothed in examples into the joint narrative. New, developed stories emerged as school leaders’ stories were validated and woven with those of mentors. Careful listening and well-timed participation created a pedagogic rhythm to construct new meanings and nuance tales of the past.

Under the right circumstances, tok stori can unlock access to understanding, knowledge and commitment. An example can be seen in a design-based research school literacy programme in the Solomon Islands. Although it looked like an effective intervention by metrics often used in evaluation, many Solomon Islanders involved in the work still thought of the approach as externally imposed. Listening to these concerns led the programme evaluators to use tok stori to intertwine the intervention with the programme evaluation. When tok stori became the mode of operation, school leaders engaged using their own familiar and shared languages, community leaders became involved through story in the programme space, and the changed relationships involved enhanced local ownership and uptake. Tok stori had led to the re-imagining of learning by local people in the form of an intervention in literacy education.

Tok stori in action in the Solomon Islands. Image credit: Kabini Sanga.

Fortunately, the scholarship of tok stori is now growing. It provides donors and policymakers with alternative ways of gaining the information vital for effectiveness. But more importantly, tok stori invites visitors into a relevant way of being with Melanesian people. The relationality involved downplays hierarchies. Seemingly technical aspects of finding out become familiar and Melanesian. Time, another key ontological construct, accommodates the storying rather than the other way around. You can’t be in a hurry when you tok stori. Being part of the group has its rewards, and its responsibilities.

Outside the office the rush is over, and darkness has come. Some friends have gone but no one else wants to leave. There is only one banana left. The stori has become a matter of who should eat it. We know that our friendship is good and we have come closer to each other through the things we have learned. No-one has said it, but we all know: to peel the yellow skin is to call it a day. Eventually, the story identifies the oldest one present as the rightful owner. As he shares the banana, we get up to go on our ways. The conference starts tomorrow and there will be another story.