Image: A school building in Solomon Islands, courtesy of Martyn Reynolds.

Everything exists in a context. Fish swim in water, humans live in families, and planets endlessly circulate in each other’s gravitational fields. When it comes to leadership, leaders are located in their local context – societies that embody and enact cultural understandings.

Leadership is therefore a contextual practice. Those who wish to support and develop leadership need to look beyond the immediate context, education for example, and see the ‘context behind the context’ – the philosophical framing that defines, legitimises, and makes sense of what effective leaders do.

In Solomon Islands, as in other places in the Oceania region, it can be helpful to think of the context in which leadership operates in three domains. These are kastom (the customary or cultural domain), church, and the institutional domain. This last includes government, formal educational activity such as schooling, and so on. The domains ‘compete’ in any given situation, and kastom is generally the strongest.

What this means is that when institutional leaders such as school leaders act, their leadership needs to be congruent with kastom and church-centred leadership as well as educationally sound. When acts of leadership separate the school leader from their community by creating ‘conflict’ across domains, they have created a context of isolation for themselves of benefit to no one.

Leadership in Context

Our leadership research has been looking at the context behind the context in three jurisdictions – Solomon Islands, Tonga and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. These states are from the regions divided by Europeans into Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia respectively. However, they are united by the advent of educational systems birthed in far off places that, to improve, must progressively respond more securely to local context, not least in leadership. Let’s explore aspects of leadership in these contexts further.

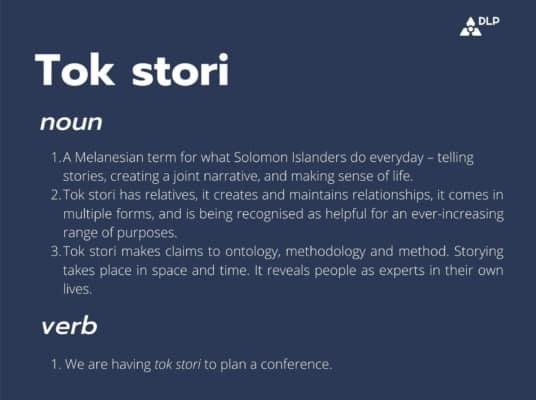

School leaders are socialised in and by their communities. In Solomon Islands, paying attention to kastom requires a relational understanding of leadership. Leaders demonstrate this through everyday actions. We were told that one school leader:

‘mentored her staff… worked to build good relationships with parents… talked with parents for them to send their children to school, and more so, offered to take care of children after classes for busy adults.’

In this context, leadership is demonstrated through care that extends after school has ended for the day. Paying attention to the church domain means that school leaders rely on

‘what they have learned in terms of important qualities and values… including being honest and fair, delegation of duties, trust and collaboration.’

One Solomon Islands school leader explained:

‘My upbringing in the church environment influences me to do things [in school] in a more God-fearing way.’

The teachings of the Church are as relevant in the school office as they are during church services.

As these examples show, community ideas of leadership travel with leaders and are not restricted to particular environments or times. A central tenet of Tongan customary leadership is fatongia. This is about

School leadership in this context centres on commitment to the group. Obligation is not a burden but an inherited pleasure, exercised in the present for a sustainable future. The chronological context of school leadership means it takes place in

‘a complex, messy, negotiable space linked to the past with our ancestors, the land and the people we have come from… as well as linking to the future, our children.’

A complex context indeed.

Metaphors are sometimes used to express the centrality of community as a context for school leadership. The RMI (Republic of the Marshall Islands) research unpacked the cultural references of kajoor wōt wōr and wōdde jeppel, which refer to collaboration, as

‘the Marshallese context of community responsibility towards student learning.’

In the RMI, we were informed:

‘This concept [is] very important when we are dealing with both community leaders and the school leaders. We can think of when we are building a canoe, and house building… it involves all the people in the community… And this relates to how we are delivering education… the concept of no child left behind also requires the whole community’s effort in raising and educating a child…’

School-based education may be a recent introduction to the RMI, but practices that have sustained communities for millennia such as building and navigation are those that provide leadership models.

Dealing with conflict

Life is seldom plain sailing and conflicts inevitably arise. Legitimacy for decision making can originate in different domains and may transcend the present. Land ownership creates kastom authority, but authority sits with the school leader’s position.

A Solomon Island school leader experienced problems when landowners expected their children to get free education and hadn’t paid school fees for many years. When a new school leader refused to accept this situation:

‘he was bashed and threatened because he enforced that every student must settle their school fees. With this conflict of understanding, the school was closed for a week because the principal had to run away to the town for safety.’

Practical and financial issues needing negotiation had arrived at the door of the new school leader.

The presence of multiple domains may frame conflict, but they also provide resources for resolution. Kastom and church leadership can step in to provide solutions:

‘[With] the beauty of having the community chief, the tribal chief and the church leaders in the community, the problem was solved, and classes resumed.’

Community cohesion and leadership from kastom and church domains are an asset to school leaders.

Contextualisation

Thinking about the context behind the context puts the spotlight on how leadership development understands contextualisation. Is this a matter of introducing an initiative, changing some key terms from one language to another and asking local people to enact the work? Or is contextualisation understood at a deep level to mean engaging with the ideas and understandings of those we seek to serve in order to learn (among other things) the limitations of our own experiences and the richness of those of others?

Where such deep contextualisation takes place and the context behind the context is honoured – involving time, commitment, careful listening, and self-questioning – leadership development is more likely to be a reciprocal experience, rewarding and of benefit to everyone involved.

This blog is based on the research brief Leadership negotiation in Oceania: The context behind the context. You can also check out the team’s other research brief on contextualising developmental leadership as Pacific Island communities understand it, Contextualising leadership: Looking for leadership in the everyday.