Image: Indian girl protecting herself and wearing a mask against the coronavirus during lockdown.

Across the world, citizens are facing extraordinary limits on their livelihoods and freedom of association. But as the initial, sharp shock of the COVID-19 crisis begins to pass, and the collective willpower to suspend productive life fades, many countries are now witnessing a worrying erosion of lockdown compliance. Looking ahead to a much messier phase of partial re-opening and selective restrictions — and over an indeterminate timeframe — governments and their leaders everywhere will be testing the limits of COVID compliance. How can they bring citizens with them on an uncomfortable but essential journey?

Whether authorities succeed or fail in enforcing potentially life-saving rules could hinge, ultimately, on whether people perceive those rules as legitimate. Why legitimate, as opposed to technically right, or enforceable? Because lockdown relies on people complying with rules that in many ways, go against their personal interests. In the early stage of the pandemic, under a prevailing climate of fear, it wasn’t hard for leaders to argue that following the rules was in everybody’s immediate interests. Now we are heading into new terrain: the future sustainably of policies will depend more and more on convincing people to do things they don’t want to do, and which therefore need a deeper, moral justification. That’s what legitimacy does.

Enforcement isn’t a sustainable solution — or indeed desirable — in situations where communities do not accept the legitimacy of the rules being imposed on them. We’ve already seen what happens when COVID lockdown has to be enforced and hastily so — as was the case in India — negatively affecting the most vulnerable groups and migrant workers. Meanwhile, authoritarians have used the opportunity to grab power. Because this is rarely going to be perceived as legitimate it is unlikely to be sustainable. Legitimate power needs to be granted, not grabbed. Absent limitless resources to coerce or punish non-compliance, the implementation of COVID rules will rely on voluntary behaviour change. Arrests for violations are neither sustainable nor an effective deterrent for the ‘refusers’, or the ‘deniers ’. We know from existing research that when individuals do not believe that laws and rules are legitimate, they will seek to bend the rules, resulting in semi-compliance at best, or break them. In our view, governments will increasingly rely on legitimate leadership to make the case for compliance; whether religious, traditional or political.

It’s already clear that COVID compliance is breaking along the faultlines of legitimate authority. We are seeing examples of authorities struggling to enforce compliance where their right to rule is contested. In Malawi, the government was forced to delay the initial lockdown because the government lacked legitimacy in urban areas. Extraordinarily, in Brazil, President Bolsanaro is actively seeking to challenge the authority of state governors to undermine the legitimacy of quarantine measures. Similar processes are afoot in the US with both political legitimacy and scientific legitimacy being challenged as ideology and uncertainty combine to produce conspiracy.

So when are rules legitimate? What are the ‘rules’ for legitimate rules? And what does this mean for how governments should be (seen to be) responding? Decades of thinking on sources of legitimate authority — from classic theory to cross-country research, and international policy debates — can be distilled into three simple ‘tests’. These are essentially the questions citizens are likely to ask themselves in order to evaluate whether they are morally obliged to comply, or not (we have spared the academic terminology, but they broadly follow the categories of ‘performance’, ‘process’ and ‘normative’ legitimacy):

1. How will it affect me?

The first, obvious question people are likely to ask about new rules is, how will they affect me? Of course, people have their own narrow sense of their interests. But beyond that, seeing that a particular policy is working, and is beneficial, could be thought of as important for legitimacy. We caution, though, that we think it’s a trap that contains the seeds of its demise and is blind to the politics of personal trade-offs.

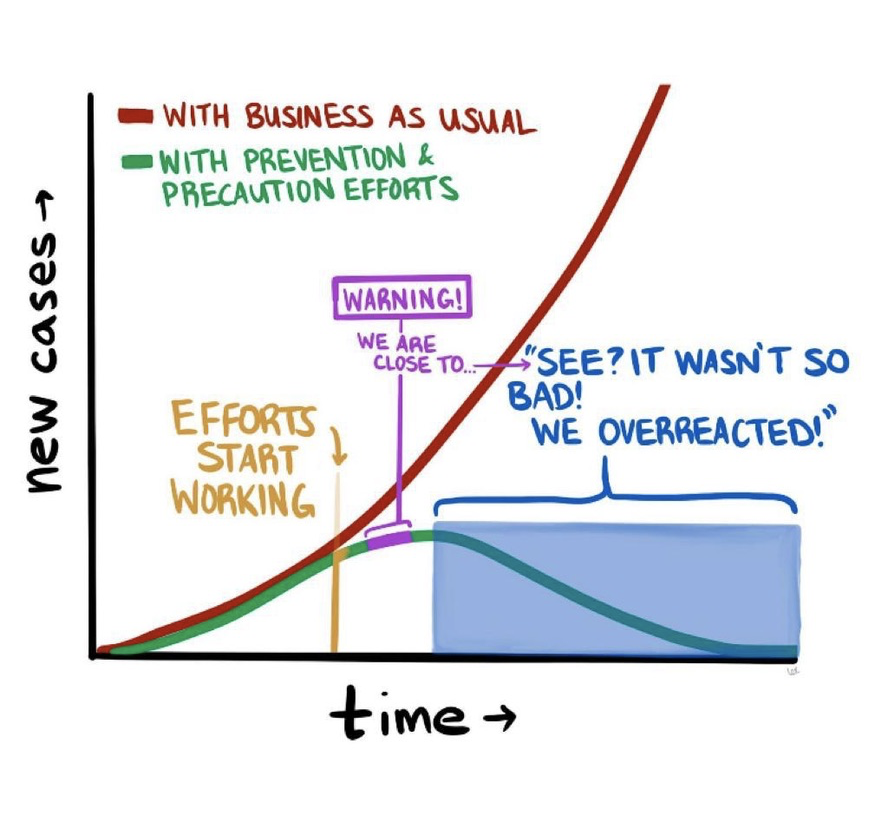

One way leaders have tried to maintain compliance is to emphasise how the social distancing measures are working to flatten the curve. This is a precarious exercise as over-egging (or even just celebrating) success can undermine public compliance with the very measures governments are trying to sustain. As humble humans, we find it pretty hard to compute counterfactuals — see the graphic for a common tendency! But it’s also the trade-offs citizens are being asked to make between their counterfactual health status without prevention efforts and how the rules are affecting their factual livelihoods!

Social distancing might be feasible for some more secure and prosperous groups in wealthier societies, but in contexts of extremely high levels of informal employment and no social security net to protect people’s income and basic needs, it is incredibly hard and unreasonable to sustain. Reporting from Lagos, Nigeria shows how uneven the compliance with lockdown is because the government hasn’t been perceived to be doing enough to meet people’s basic needs. Some have argued that lockdowns are only legitimate as long as people are compensated. But as time goes by, compensation is not likely to be enough; research tells us that ‘outputs’ alone are not enough to convince people to follow the rules. People need more than their own interests satisfied.

2. How was it decided?

Especially when the rules don’t benefit people personally, people tend to look for reason in how those decisions were made, or by whom. They might ask who was included or excluded, whether there was due diligence, transparency or accountability. This test is particularly salient for COVID compliance because there is substantial and robust evidence — stemming from Tom Tyler’s path-breaking work — that people can accept decisions that go against their direct interests (i.e. loss of livelihoods and freedom) if they believe that the process of decision-making was fair.

But when are emergency lockdown decision-making processes likely to be seen as fair? Traditional political theory tells us that at a minimum, legitimate rules need some basis in law. The problem is that legality can become incredibly fluid (and exploited) in unprecedented ‘states of exception’ or emergency.

There is understandable disquiet that many states are using the elasticity of crisis to stretch or circumvent the ordinary procedures of government – whether through emergency laws, strengthened executive powers, or special committees. Governments are effectively asking citizens to take their decisions on trust, and in the scramble to meet the most urgent needs, transparency and consultation are the first casualties. And in contexts of low trust and legitimacy to begin with, this is a fragile state. In Malawi, the recent high court decision to temporarily bar the government’s lockdown highlights this tension. The protests that erupted across the country, from market traders and health workers, were precisely because President Mutharika and his government were not trusted to protect the interests of the poor during the lockdown.

The problem with the legitimacy of decision-making processes in an emergency is that social tolerance shifts and a lot more discretion can be justified. The question then becomes, how far can societies’ tolerance of rule-bending be pushed? Part of the answer lies, ultimately, in whether the rules are seen as serving the public interest. There is a fine line between justifiable emergency measures and unjustifiable power grabs that undermine perceptions that the state is acting in the interests of the people. The urgency of crisis cannot justify wide margins of executive discretion indefinitely. But for now, expecting governments and leaders to build compliance through consultative and transparent processes looks rather fanciful.

3. Why is it the right thing to do?

If the first two tests aren’t enough to induce voluntary compliance — which looks increasingly likely — the next question people might ask is the big one — ‘why are we doing this?’ In other words, what’s the normative justification for it? People need more than self-serving justifications to make big sacrifices to their lives. Humans are driven by social motivations that go beyond the material. They are more likely to comply with rules that don’t benefit them if they have some basis in shared values and beliefs. The same applies to COVID compliance, which ultimately needs to find the same justification.

Compliance will likely hinge on the moral power of the ‘why’. This was illustrated pretty starkly in a recent study of citizen compliance with lockdown in the US. Here, perceived threats of punishment, or the costs associated with complying with the rules (i.e. personal interest motivations) had no effect on compliance, whereas levels of moral support and supportive social norms (i.e. social motivations) increased compliance.

What this implies is that people need to buy into the norms and ideas behind the lockdown rules. Ideas — big and small — are ultimately what justifies policy choices and makes them legitimate. Framing and narrating the rules in ways that tap into deeply normative ideas and public sentiments about what is right for society is therefore likely to be key. It’s no coincidence that in the UK ‘stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives’ has been the dominant narrative used to generate social consensus. By normatively framing the NHS as something to protect, political elites are tapping into some of the shared values and ideas that form part of our national identity — universal rights, everybody gets a fair share – to reinforce the moral basis for compliance.

Legitimacy will fade, and compliance will break down, wherever there is a perceived conflict between the rules and the dominant belief system: whether legal, religious, or cultural. In the same way that it threatens legitimate authority, perceived unfairness poses a real threat to COVID compliance. Since governments and leaders need voluntary compliance, they need to cultivate, play to, and most importantly not violate the shared beliefs that underpin society.