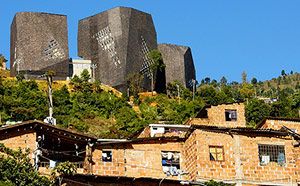

Image: ‘Medellin’ (Miguel Olaya, Flickr).

Since my DLP paper on Medellín was published, the city has become a ‘model’ for development – offering a palette of policies to combat urban violence that can provide a blueprint for cities with similar problems.

Medellín was awarded the 2013 award for Most Innovative City, and was host to the World Urban Forum in 2014. This is indeed a remarkable transformation – Medellín was once the most violent city on earth, and home to the world’s most powerful and notorious drugs cartel, run by Pablo Escobar. Yet, from a peak of 375 murders per 100,000 of its citizens in 1992, the city has dramatically reduced violence to levels that are now comparable to those of North American cities.

Image: Medellin’s Santo Domingo Savio Library (Tomas Botero Vargas, Flickr).

The now common narrative is that this was achieved through urban development policies that were aimed at addressing the inequality and exclusion thought to be behind the violence. These policies included extending the metro system, with cable cars going to the most stigmatised areas of the city, and establishing inclusive public spaces such as parks, art galleries and museums. Some of the world’s best architects were asked to build libraries strategically placed in areas that had once been no-go zones.

However, the popularity and prominence of the Medellín Miracle has become a concern to many. They fear that the visible bits and pieces that supposedly made the ‘miracle’, the transport system, parks and iconic buildings, have been reduced to a branding strategy for the city in the global market place – and that the political changes behind the miracle are being forgotten. It is also frequently, and powerfully, alleged that the reduction in violence in Medellín has more to do with the power granted to paramilitary groups to control violent areas – what Forrest Hylton has termed a ‘paramilitary peace’.

It was in this context that I returned to the work I’d done in the city in 2012 to develop a book on the political lessons of Medellín’s transformation. The main contention of this book echoes the DLP’s approach to development; this has not just been a technical fix, and the political changes behind social urbanism are an essential element of understanding what has happened in the city.

For Medellín’s transformation was anything but an overnight ‘miracle’. The political coalitions and networks that made the policies of social urbanism possible took decades to develop. On being declared the most violent city on earth in 1992, political actors – politicians, community leaders, academics and business leaders – were galvanised into a search for ‘Future Alternatives for Medellín’. Seeking to understand what was behind the city’s astronomical levels of violence, they held a series of seminars. Their analysis was that pervasive inequality and exclusion in Medellín had flourished in the context of Colombia’s on-going civil war and the economic recession of the 1980s. This had allowed violent actors to gain power and to abuse it.

The main coalition that formed during this process of analysis between social movements, NGOs, politicians and business elites was eventually to become a political party – Compromiso Ciudadano. Compromiso Ciudadano won the municipal elections of 2003 and, under the administration of Mayor Sergio Fajardo, was able to implement the policies of social urbanism that had been developed during the previous decade.

The real lesson from Medellín is how political processes changed. And these processes, fear many of the progressive actors involved with the development of social urbanism, are now at risk. They fear that calling their success the ‘Medellin Model’ implies that the city’s transformation was a technical fix. Yet behind the ‘blocks of concrete’ – as one community leader referred to the iconic buildings that have re-branded the city – progressive and in some cases radical social movements and NGOs worked to form coalitions with Medellin’s exclusive political and business elites. Those elites were themselves committed to addressing the astronomical levels of violence experienced in the 1980s and 1990s.

These coalitions were made possible by inclusive political processes and by checks and balances to attenuate the potential for populism. Innovative strategies encouraged the creation of co-operatives, community-business alliances and platforms so that the perspectives of everyone in this astonishingly diverse city could be understood, including radical and minority groups.

The Medellín Miracle is not about the architectural and infrastructural transformations, but the long term political changes that made it possible for the architects and engineers to build them.