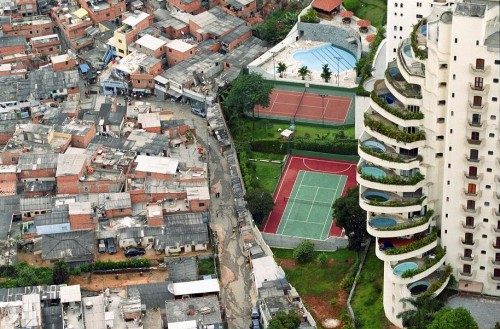

Image: Favela de Paraisópolis (‘Paradise City’) within São Paulo’s wealthy Morumbi area (Photo: Tuca Vieira, 2007).

From the Occupy Movement to Thomas Piketty to current proposals for a new set of Sustainable Development Goals, inequality has emerged as one of the most intractable challenges of our time, and everyone, from activists to academics to policymakers, is talking about it.

Yet despite all the attention, discussions on inequality have so far paid little attention to the underlying politics that help sustain it. At its core, making development more inclusive and broad-based involves altering existing power structures and dynamics – it entails not only growing the size of the pie but also (re)allocating the slices, as my colleague David Hudson has put it.

How – and whether – this can be done was the theme of the second annual DLP conference held in Birmingham last week. It is also the focus of a collaborative DLP research project that Duncan Green introduced at the conference.

The conference helped to crystallise that tackling inequality is not simply about “getting policies right” from a technical perspective, but about identifying policies that are politically viable given a particular context, and seeking to align interests and incentives in more progressive directions. A mixture of different institutional, agency, structural, and economic factors have been essential in facilitating more equitable and inclusive development across time and place. Here are my main takeaways from the day.

- Critical junctures can provide important momentum for internal transformation. These can include, for example, peace agreements to end violent conflict, or participatory constitution-making processes, or a particularly critical election, as well as (external) threats and exogenous shocks.

- The nature of political settlements and whether the balance of power among different groups favours or inhibits redistributive reform will define the contours of what is possible. Political settlements are of course dynamic and change over time. But as Sarah Hunt from the University of Manchester told us, in Honduras former President Manuel Zelaya was ousted in 2009 because his plans for reform were deemed too radical, even though they were in fact rather modest. This shows how limited the potential for transformation is when key elites (in this case political, economic and military elites backed by powerful international actors) oppose it. Early land reform was a crucial factor in the eventual, more evenly shared transformation of the so-called East Asian tigers because it broke the back of entrenched landed interests. This never happened in Latin America, and land concentration remains one of the root causes of persistent inequality in the region. As we learned from Sian Herbert from the GSDRC, while efforts to address inequality in Brazil over the past two decades have been impressive, they have so far only scratched the surface of underlying power structures. Tellingly, at number 13, Brazil still is one of the most unequal countries in the world.

- While structures may define the boundaries of what is politically feasible, committed political leaders, both within and outside the state, can push those boundaries. Leadership is needed to identify the possibilities and the constraints for adopting policy reforms, navigate through competing groups within and outside the state, and build possible reform coalitions on the basis of negotiation, bargaining and contestation.

- Political parties have emerged as essential in facilitating collective action and overcoming obstacles to pro-poor reform. The Workers’ Party (PT) in Brazil and, historically, the Communist Party in Kerala are well-known examples of this. Interestingly, many such parties have their roots in social movements with a long history of seeking to alter the balance of power from the bottom up. This is true of the PT, of course, but the social mobilisation behind Evo Morales is also noteworthy, as Duncan Green reminded us. The experience of Dalit women in Nepal, which was shared by Abigail Hunt from Womankind, highlighted the important role that women’s mobilisation and organisation have played in exerting pressure for greater inclusion. However, that case also showed how other dimensions of inequality, such as ethnicity or caste, need to be addressed if more substantial change is to be achieved. This echoes the findings of a recent Development Progress study of women’s empowerment in Tunisia.

- Ideas and ideology matter too, especially when they help define or invent a sense of nation (think of Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” in the aftermath of the invention of the printing press); and establish what kinds of identities are used for mobilisation and action or as fault lines of exclusion. The experience of Rwanda that Pritish Behuria discussed is a vivid example of this – both before and after the genocide.

- But in recognising the centrality of politics in understanding inequality, we should not overlook the economy, as Frances Stewart made clear. Several aspects of this demand further investigation. For instance, do episodes of growth need to come before successful redistribution efforts, as appears to have happened in Brazil? And is there something about the structure of an economy that will make it more or less likely to encourage inclusive development? Zainab Usman showed that economic diversification in Nigeria has benefitted only very specific sectors and areas of the country (namely in the South and coastal areas), and this has further entrenched inequalities – and conflict. In Mauritius, on the other hand, the shift from an economy based on sugar to one based on textiles has helped to generate more widespread and evenly distributed growth.

So the possibilities for progressive change will depend on whether an effective combination of institutions, leaders, parties, interests, incentives, ideas, and pressures from both above and below can come together.

Even then we don’t know how processes of change and transformation will pan out. Multiple trajectories of institutional transformation are possible, but they are likely to be messy, involve difficult dilemmas and trade-offs, and are bound to be constantly negotiated and contested.

Indeed, transformations have often proved to be tumultuous and violent. This prompted Heather Marquette’s provocative question – are we trying to cheat history by thinking it is possible to engineer processes of change that remain violence free? The fate of the Arab uprisings, where only Tunisia seems to have turned the corner, certainly gives pause for thought.

Pathways and outcomes are by no means predetermined or predictable. Much will depend on contingency and, yes, even luck – a fortuitous alignment of the stars that always has the potential to go more than one way.